Voices of the Earth

5 years of “realtive” peace in Colombia

5 years of “realtive” peace in Colombia

Journalists are one of the groups most persecuted by the Daniel Ortega government, according to an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACH

We begin this article with the words of Martha Cabrera, a Nicaraguan psychologist who stated that “as Nicaraguans we carry painful baggage,” loaded with individual and collective mourning and traumas. This powerful statement does not stand alone. According to Cabrera we are also “a society with a history that is hard to swallow” and “a culture of silence and blocked tears.”

The baggage we refer to is heavy with pain, provoked by systemic social and political violence, marked by cruelty and impunity promoted at the highest levels. This violence has created a society marked by an unending cycle of repeated human rights violations that does not allow for advancements in the construction of a country based on justice, democracy, and freedom.

Due to this state policy, between 1821 and 2021 there have been 52 political amnesties and pardons in Nicaragua. The last of which was Amnesty Law 996, passed in June 2019. All have different characteristics and contexts but the same aim: to put an end to armed conflict or settle rivalries between powerful elites without addressing injustices. None have contributed to solidifying the rule of law, strengthening democratic institutions, or establishing mechanisms for an independent and rights-based judiciary, among other reasons because none have produced peace with justice.

On 15 September 2021, Nicaragua commemorated its bicentennial. With balloons, parades, and speeches it celebrated its independence, the beginning of the republic, and having broken away from the Spanish crown. However, in 200 years we have not been able to break out of or break down the culture of violence and impunity, consolidated three years ago under the Sandinista government, which not only promotes, but even rewards impunity. Hence, there is no independence for us to celebrate.

In fact, the social protests that began in April 2018 against the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo government originated out of social discontent over our government’s anti-democratic and authoritarian practices. The situation intensified in 2007 when the Sandinista Front came back into power and took another twist in 2018 with the establishment of a police force focused on the absolute prohibition of the right to protest, the criminalisation of social protest, and a state policy of repression of dissident voices.

Since 2018, as Nicaraguans we have been victims of and witnesses to brutal repression, actions that constitute state terrorism, and crimes against humanity such as extrajudicial killings, torture, and enforced disappearances. The Nicaraguan government has not placed limits on the use of repression to undermine and silence the population’s voices through the use of terror.

These legitimate protests and their violent state repression resulted in the lives being taken of 328 individuals, according to the Centro Nicaragüense de Derechos Humanos (CENIDH - Nicaraguan Human Rights Center). Thousands were injured due to the use of lethal weapons against the population. Up to December 2020, 1,614 individuals were arbitrarily detained according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and there are currently over 150 political prisoners and at least 108,000 people in exile. The state response was accompanied by an official discourse denying these crimes, while forcibly persecuting dissident voices and victims who demand justice, accusing them of terrorism, treason, and seeking to destabilise the country.

In September 2018, the population witnessed the promotion of Capitan Zacarías Salgado, one of the people responsible for “Operación Limpieza” (Operation Clean-up) in Masaya, which resulted in dozens of murders since June of that year.[1] Three years prior to the operation, Salgado was accused, convicted and sentenced to 11 years in prison for a massacre in the Las Jaguitas de Managua community. This was a police action that led to the violent death of three family members, including two children, and injuring three others. Despite the conviction, it is unknown if he ever went to prison. Three years after these incidents he appeared leading the attack in Masaya and, in September 2018, Ortega promoted him to Commissioner. Salgado acted as second in command of the Rapid Response Troops (TAPIR - Tropas de Intervención Rápida), an elite group of the Police Special Forces accused of human rights abuses.

Also, in the context of the Police Forces’ 42nd anniversary in September 2021, Daniel Ortega decorated six police commanders with the Rigoberto López Pérez distinction. All of them had international convictions, are loyal to the president and his family, and all of them were accused by different entities of serious human rights violations.

Regardless of the Nicaraguan government’s efforts to silence victims’ voices, in different ways and some, even from exile, have continued to legitimately demand justice. In contrast with other historical moments, when silence was imposed and socially accepted, this time victims are not willing to go on with blocked tears and injustice lodged in their throats.

The Human Rights Collective for Historic Memory in Nicaragua (“Nicaragua Nunca Más”) was created in 2019 by human rights defenders in exile in Costa Rica. They accompany victims of repression in Nicaragua. In just over two years they have managed to document 600 cases, including the testimonies of 108 victims of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatments.

It has not been easy. Documenting from exile implies huge challenges, specifically considering the pandemic context, increased repression, and a lack of political will from the Nicaraguan government in the face of calls from the international community. The international community has repeatedly insisted that repression stop, that the police force be disarmed, and that rule of law be reestablished. Despite this difficult context, at the Collective we are committed to continue documenting violations, not only in preparation for future legal cases, but also as an antidote to oblivion.

It is essential that the state acknowledge the crimes committed, as are investigations to make possible the clarification of incidents, the identification of responsible parties, access to justice, redress for victims, and the provision of guarantees of non-repetition. Along this journey, documentation is an essential step towards collective healing. The construction of a country with justice, freedom, and democracy, the country that the Nicaraguan people deserve, depends on this process.

Juan Carlos Arce Campos | Colectivo de Derechos Humanos Nicaragua Nunca Más

[Photos: Delphine Taylor]

[1] Due to the repression, in April 2018 barricades or blockades were put up in the country’s main cities in urban areas and on the principal roadways. They were built by the population in protest and as a defence mechanism against attacks by the police forces. In June of that year the government organized a unit made up by the police forces and around 5,000 armed civilian (para-police), armed with military weapons, which were used to repress protestors to open the road and disperse the protests. Around 170 individuals died during that period (June-July).

It is not easy to determine when the PBI-Nicaragua project started. Was it when the first person or group identified a need? When the first official request for support was received? Or when the team on the ground took up their posts and started to get things moving?

In April 2018, when life in Nicaragua was forever changed by the disproportionate use of force and violence by police and para-police forces against peaceful demonstrations, several people within Peace Brigades International (PBI) and close to the organisation asked themselves: “should we do something?”. Shortly afterwards, and in response to a growing number of requests for help and support from individuals and organisations facing direct threats from the authorities and vigilante groups, a small group of PBI volunteers and staff met and formed a committee to investigate the situation and formulate a proposal.

A first visit to Nicaragua in November 2018 quickly revealed that there was no possibility of establishing a project within the country, due to the level of repression and the inability of organisations to operate openly. All meetings, demonstrations or acts of protest were repressed; the offices of many organisations were closed, and large numbers of people were leaving the country for Costa Rica or further afield. It became clear that if PBI was going to support Nicaraguan human rights defenders and their organisations, it would have to be from outside of the country.

In early 2019, two committee members visited Costa Rica and spoke with many newly arrived Nicaraguans and others working with the exiled community in San José, exploring ideas about what PBI could do to alleviate the terrible reality of a growing population of asylum seekers and refugees, many of whom had left home and family, in fear and with few possessions, abandoning or having lost their professional jobs or their university studies and academic credentials. People were living in uncertainty: they did not know how long this would last. The need to come together with others in similar circumstances was clearly evident.

There were two main observations: firstly, in the face of the massive arrival of Nicaraguans in Costa Rica, there was a marked lack of capacity of other NGOs or international agencies providing protection and humanitarian assistance to respond to the basic needs of shelter, food and medical care.

This contrasted with what was happening in other countries experiencing a large influx of asylum seekers, where the host country turned to agencies such as the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) or others for assistance.

In the first few months, it seemed that Costa Rica tried to minimise the number of arrivals and the necessary mechanisms were not put in place. This added to the uncertainty of the exiled Nicaraguan community. Secondly, people found it difficult to come to terms with what had happened to them and to identify how to move forward.

It became clear that PBI could respond to this situation by formulating a project that was different from the organisation’s traditional model of providing a physical presence to accompany individuals and groups facing an immediate threat to their lives or freedom from the authorities or other groups in their own country. This time, it was important to provide a psychologically and socially safe space for people to process what had happened to them, and to begin the process of building social and community structures for their own support and in support of those they had left behind in Nicaragua. This would require a new model of accompaniment, and the committee set about designing a programme and seeking the necessary financial and logistical support.

Physical-political accompaniment in this context was not necessary, but accompaniment through capacity building was identified as important, considering three strategic areas of work:

Organisational strengthening: in order to structure and strengthen initiatives in exile, and those that were already doing hard work in the defence of human rights, helping to create meeting spaces and address organisational issues such as communication, the sense of belonging, motivations for being part of the collectives, among which the most important thing is to come together, recognise each other, and begin dialogues.

Protection / self-protection: taking into account that even in Costa Rica there could be situations of risk that constitute a threat to the Nicaraguan diaspora. On the other hand, knowing that there are still many organisations in Nicaragua that are still living through situations of risk, and through those in exile, they were able to access training spaces that provide them with self-protection tools.

Psychosocial accompaniment: socio-political violence leaves its mark on society as a whole, and exile continues to be one of the impacts, meaning it is important to re-signify experiences and rebuild personal and collective life projects. PBI seeks to contribute by strengthening personal and collective tools to help support Nicaraguan human rights defenders.

In the first months of 2020, the project had two full-time staff members, of which only one remained in San José for part of the initial year due to the coronavirus pandemic. Despite the fact that all workshops and training sessions had to be conducted online and that groups and opportunities for informal face-to-face meetings were impossible, the team went ahead and built relationships with and between groups, including the Movimiento Campesino, the Bloque Costa Caribe en el Exilio, as well as a women’s group and a university youth group.

In 2021, we continued the virtual work in the first quarter, gradually generating formal and informal face-to-face spaces. Meeting each other has been fundamental. Our work continued with the aforementioned groups, and gradually incorporated others such as the University Coordinator for Democracy and Justice, the Pinolera Women’s Network, youth groups, specific support for journalists, as well as strengthening ties with organisations already established in exile and those working in the same way to contribute to strengthening the social fabric of the Nicaraguan diaspora in Costa Rica.

At the same time, an advocacy and communication strategy was implemented, expanding capacity building actions and at the same time generating visibility of the situation of Nicaragua and exile at the international level.

With PBI’s participation in different platforms and the constant coordination of actions with national groups in Europe and the United States, we have promoted the participation of different defenders in exhibitions, debates and exchanges with international representatives, strengthening their messages and in some cases facilitating access to these spaces.

Although the training sessions and workshops have been the most visible aspect of the project, those working with frontline human rights defenders will recognise the important contribution that an international accompaniment organisation such as PBI can make by its presence alone. Both individually and organisationally, the people we work with appreciate the support we provide, the recognition of their situation, the importance of international links and the visibility we can provide.

As the project moves into the next phase in 2022 and 2023, it will be this direct advocacy and communications work, carried out by the Nicaragua-Costa Rica project together with the many PBI groups in the region, in Europe and elsewhere, that will help give much needed ‘visibility’ to what has happened in Nicaragua, and what the many exiled Nicaraguans want to see recognised by the international community.

As an organisation, let us hope that we do not fail them.

PBI Nicaragua in Costa Rica

[Photo: Gabriela Vargas]

In the community of Siempre Viva a large cloud of smoke appears that begins to disperse and obscure the area’s natural landscape. The Río Indio gradually becomes cloudy and stops reflecting the typical sun of summer in the municipality of San Juan, Nicaragua. On 3 April 2018, an alert from the Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities informed us of a forest fire in the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge that would rapidly move towards the core area of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve.

From this moment on, public alarm arose over what was happening in this area, far from the Nicaraguan capital. Media and social media began to communicate the news. Nobody knew that we were facing an event that would change our country’s history. The hashtag #SOSIndioMaiz began to go viral throughout Nicaragua. It was like the awakening of citizen environmental awareness.

The fire was of great concern for three reasons: first, because the forest in the area had suffered the impact of Hurricane Otto in November 2016, which left a lot of fallen vegetative material; second, because we were in the dry season, when temperatures rise and there is less frequent rain; and third, because winds were constantly fanning and rapidly moving the fire towards the interior of the reserve. In other words, it was the perfect storm for a fire to spread and turn everything in its path to ash.

The Fundación del Río began to publicly demand state action to attend to this emergency and to declare a yellow alert in order to have all necessary capacities to stop the advance of the fire. The state’s initial response, however, was silence, denial, and a minimisation of what was happening. This outraged the capital’s young university students, who took to the streets to show their disapproval of government neglect.

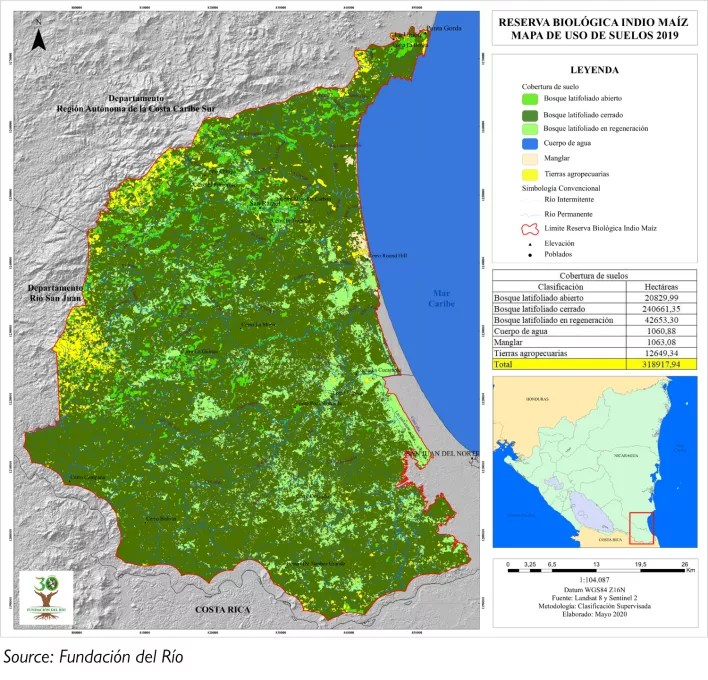

In the years before the fire, alarm had already been raised about the deteriorating situation in Indio Maíz, the second most important forested area in the country with 2,639 square kilometers, almost the size of the city of Madrid, Spain. Complaints about the invasion of settlers (invaders), land trafficking, deforestation, livestock, gold mining, and the construction of infrastructure were positioning themselves in the consciousness of the Nicaraguan population thanks to the diverse voices of the Rama Indigenous peoples and Kriol Afro-descendant communities (owners of 70% of the reserve), and local environmental organisations working in the area.

For this reason, when the first protests by young university students began in Managua, other societal groups came together in the streets, in such a way that the feeling of repudiation radiated in other cities, such as Matagalpa, where organised youth also protested. The government’s response to these demonstrations was violent and aimed to silence the demands of these groups through harassment and repression carried out by mobs linked to the party in power, forming part of the immediate antecedents of the socio-political and human rights crisis that we are experiencing in Nicaragua.

While this was happening more than 400 kilometers away from the fire area, the risk developed of losing the enormous biodiversity in Indio Maíz. The reserve is home to about 369 plant species and about 550 species including amphibians, reptiles, mammals, birds, and insects. Much was to be lost in an area that is part of, and connects, the Central American and Mesoamerican Biological Corridor. The government had no choice but to acknowledge, albeit belatedly, the emergency situation in the area, all thanks to social pressure and the advocacy of environmental organisations that demonstrated the fire’s advance on satellite maps.

During those tragic days of April 2018, the mobilisation of Nicaraguan Army brigades to the area was not enough to stop the spread of the fire that crossed rivers and ecosystems, drastically changing the existing green landscape. National capacity to tackle the fire was very limited; the country had not invested in preparations for this type of event. For this reason, the public call of #SOSIndioMaiz was made to ask for solidarity and international support. Several countries answered this call, including Costa Rica, mobilising a specialised forest fire unit. However, on 9 April, the Nicaraguan government rejected the collaboration offered by Costa Rica to fight the fires, again fueling the population’s social discontent.

Even though delayed national efforts and international solidarity helped neutralise the fire, it was not until 16 April 2018 that Mother Nature sent enough rain to eliminate the last strongholds of the fire in the area. The fire burned some 6,788 hectares of humid tropical forest and Yolillal ecosystems. The presumed origin of the forest fire was determined to be uncontrolled agricultural burning by a farmer who was allegedly illegally occupying part of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant territory, a phenomenon that, since 2009, has been intensifying, according to the Rama and Kriol Territorial Government.

Three years after the fire, the deteriorating situation of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve continues, and while the government made an “urgent call to preserve and recover forests as the best way to face climate change” during the Climate Vulnerable Forum on 2 November 2021 at the COP26, Nicaragua is the country with the fastest deforestation rate in the world. In the Indio Maíz Reserve, denouncements of invasions, gold mining, and the advance of livestock areas within its core area are a daily occurrence. The last map made by Fundación del Río shows that in 2020, 23% of the forest was deforested, degraded, or in natural regeneration. However, 76% of the forest is conserved, thus keeping alive the hope of continuing to fight for this important natural reserve, as well as of maintaining the spirit of environmental awareness that was awakened among citizens in April 2018.

The Nicaraguan state’s repression of land and human rights defenders has positioned the country as the deadliest in the world per capita for the defence of the environment and land in 2020.[13] The model of criminalisation used against environmental rights defenders in Nicaragua is repeated in many countries, where raising one’s voice means exposing oneself, or even having to move or go into exile to protect one’s physical integrity. We must continue to denounce the governments’ actions on environmental matters and contribute to creating a context for just development so as to avoid ongoing adverse impacts on ecosystems, territories, and communities.

Amaru Ruíz Alemán | Fundación del Río

[Photo: Otto Mejia]