The 2018 social uprising in Nicaragua brought the civilian population together to demonstrate in the streets. Despite the great difficulties and inequalities faced by LGBTIQ+ people in Nicaragua, they were visible among the thousands of protesters who attended each march, a milestone within a milestone.

However, outside their participation in countless struggles for human rights, discrimination against LGBTIQ+ people is visible in all spheres: “[B]eing a gay, trans, or lesbian person became an ordeal […] in the public life of the country.”

Amid adversity, organisations that work to defend the rights of the diverse community have managed to reveal the persecution and stereotype-based violence suffered by LGBTIQ+ people. They have shown that most acts of violence against LGBTIQ+ people are perpetrated by state institutions, such as the Ministry of Health and the National Police which, rather than ensuring a protection of all citizens’ well-being, they stigmatise them on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, and dissident bodies.

Potential indicators or alarms of violence towards the diverse community in the context of a sociopolitical crisis becomes even more evident in acts fuelled by hate, contempt, and discrimination over non-compliance with the traditional system’s norms, and above all for raising voices of dissidence against the Nicaraguan government’s arbitrary actions.

In 2019, the Mesa Nacional LGBTIQ+ Nicaragüense (National Nicaraguan LGBTIQ+ Coalition) presented the “Informe de Afectaciones a las Personas LGBTIQ+ en el Marco de las Protestas en Nicaragua” (Report on Impacts to LGBTIQ+ People in the Context of Protests in Nicaragua) in Costa Rica, compiling the anonymous testimony of more than 200 LGBTIQ+ people who were attacked by people close to the Nicaraguan government.

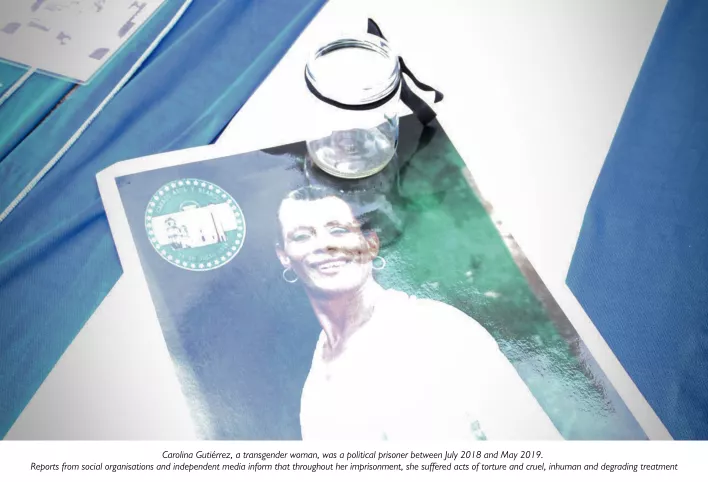

The same report reveals more than 18 impacts ranging from remote access to social media accounts to rape or murder, all accompanied by hate speech regarding sexual orientation and gender identity. It also reveals the cases of three transgender women who were imprisoned in male prisons, a violation of the integrity of their gender identity by state authorities.

In this context, many people from the LGBTIQ+ community were forced into exile; if before the sociopolitical crisis in Nicaragua their human rights, such as the right to a life free of violence and discrimination, could not be guaranteed, this is even less so in times of sociopolitical crisis.

Resisting from exile

In 2019, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) presented a “Preliminary Study of Nicaraguan Mixed Migratory Flows between April 2018 and June 2019”. Of a sample of 491 people, 4% identified themselves as part of the LGBTIQ+ community. Although 86% of these people said they felt safe in Costa Rica, housing conditions had worsened for 57% of them. Access to sources of income through decent and stable work to meet the needs of housing, food, healthcare, and education has been one of the main challenges faced by the Nicaraguan population in exile. Added to this situation is the current context of global pandemic that has highlighted inequality rates, worsening their living conditions.

In Costa Rica, exiled LGBTIQ+ people continue to resist, each one as they are able, and, at the same time, to organise emotional support for one another as they seek aid from humanitarian and human rights empowerment frameworks and respect for their identities and integrity based on their immigration status as refugee claimants.

Among the Nicaraguan groups that have sprung up in exile we have Mesa de Articulación LGBTIQ+ Nicaragüense en el Exilio (Coordinating Committee of Nicaraguan LGBTIQ+ in Exile- MESART) a coordination and communication space for people of diverse sexualities and non-binary genders that aims to serve and strengthen the LGBTIQ+ community in exile in order to identify and respond to its humanitarian, labour, and legal needs.

The community of diverse Nicaraguans exiled in Costa Rica stands firmly behind the defence of human rights, participating actively and autonomously for a Nicaragua with justice, democracy, and freedom. Some of the actions that MESART has promoted have to do with resource management: financial support for housing payments, giving out food, hygiene, and COVID-19 protection kits, psycho-emotional accompaniment, referring cases to allied organisations, know your rights empowerment spaces, activism, and digital, social network campaigns on awareness about discrimination, gender inequality, a culture of respect, and of course the situation of human rights violations in Nicaragua.

To provide support to diverse communities in exile, MESART has woven networks to help it provide support to LGTBIQ+ people. Valuable actions have been organised with organisations such as Cenderos - Centro de Derechos sociales de las personas migrantes (Center for the Social Rights of Migrants), Colectivo Colmena de las Brujas, Red de Mujeres Migrantes (Migrant Women Network), TCU-Migraciones (from the University of Costa Rica), Fundación Acceso (Access Foundation, and Voces Fieras (Fierce Voices); as well as with international organisations such as RET, UNHCR, and HIVOS Latin America. These are some of the alliances that have allowed us to provide greater support by bringing together and positioning diverse voices.

MESART is committed to human rights and to the people who ask for its support. Its local credibility is born of and for Nicaraguan LGBTIQ+ people in exile.

“The best way to build the future is by uniting a diversity of forces.” This is a belief for which the entire Nicaraguan community has fought and that breeds hope for a common good.

Mesa de Articulación LGBTIQ+ en el Exilio

[Photos: Víctor Manuel Pérez, Fransk Martínez]

This article is part of PBI Nicaragua in Costa Rica’s publication “Nicaraguan voices in resistance”, a project that unites different voices from Nicaraguan exiled human rights defenders. It is a tribute to the Nicaraguan organisations and collectives that, from exile, work continuously in the defence of human rights, bringing together the voices and testimonies of those who promote this work through non-violent action and in a culture of peace.